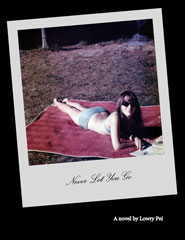

Never Let You Goby Lowry Pei

One thing you can’t help learning about life is that most of the time it puts up a lot of resistance, as if you were trying to write a passionate love letter with a pen dipped in molasses. And yet every once in a while the resistance decreases.

It did that from one day to the next during the January of my senior year in high school—the stuff things were made of softened and began to flow in unpredictable directions.

It did that from one day to the next during the January of my senior year in high school—the stuff things were made of softened and began to flow in unpredictable directions.

At the time, I was listening to Ray Charles and John Coltrane every chance I got, I liked to read Dostoyevsky late at night, and I felt as though my balls might crack from internal pressure. The girls I knew at school seemed to think that getting good grades meant I shouldn’t want what their boyfriends wanted—but I made a hell of a confidant. If I couldn’t have a love life with them, at least they could tell me the truth about the ones they had. I had years of practice at that, with Toni Anastos, Claire Joseph—who once was my girlfriend, not for long enough—and more recently with Becca Shulman. I spent at least half an hour every evening on the phone with one or another of them; we squeezed the day ruthlessly for every drop of meaning. It would have thrilled Mr. Kearns, the AP English teacher, if only we’d been doing it to Shakespeare. Those were conversations I couldn’t have with boys, other than my best friend Dal, because if I tried to have them, all I got were variations on “Didja get to second base?”

Dal’s real name was Darryl, but that had last been heard some time in grade school. Even his parents called him Dal. He was a terrific ballplayer—when Dal was in Babe Ruth League he made the all-star team—and when you saw him playing baseball you seemed to see exactly who he was. He was a center fielder, responsible for an expanse of open grass that he could somehow cover without seeming to make an effort. He never looked bored out there; he looked as intensely involved as the shortstop, but in a different way, as if the real game were one nine-inning-long thought, from the first pitch to the last out. At times it seemed as though everyone else played inside Dal’s idea of ball. He looked pure to me—not just on the field. Maybe that was making too much of him, but maybe it wasn’t. There’s something in some people, like Dal, that puts ugliness to shame. And he played life the riskiest way; he just was. Whereas my other friends had plenty of defenses, that let you know they thought they were living in a difficult world. Well, didn’t all of us? All except Dal.

In the seventh grade I was four foot eleven, which made me the shortest kid, boy or girl, not just in my home room but in the entire seventh grade. It was typical of Dal that he didn’t care about that. Other kids made jokes about stuffing me into lockers or even wastebaskets and now and then some giant eighth-grader would try to do it, laughing as if he were the very first dipshit ever to think it up. Of course those guys had about as much electrical activity in their brain as my cat, so it was a red-letter day when they had any kind of an idea at all. The only things I had going for me were I could run fast, I could talk fast (though talk is useless with your average thirteen-year-old hood), and if I could just manage to stay calm I had a certain talent for making myself invisible. It’s one of the things I learned as a little kid that came in handy later on.

They didn’t try stunts like that when Dal was around. Not that he was my bodyguard; it was just that even those clowns would have felt stupid doing something like that in front of him. I’m not sure they actually knew where the influence was coming from, but I did.

Dal wasn’t crazy about talking on the phone, or I might have spent another hour talking to him every night, after I quit talking to Toni or Becca or Claire. We had something else we did instead. Every once in a while, at one in the morning, I would get dressed and sneak out of my house, go down the block to my car which I would purposely have parked far away so my parents wouldn’t hear it when I started it up, and drive to Dal’s. Maybe they wouldn’t have been waked up by the grinding starter of that old three-hundred-dollar Ford, but I wasn’t taking any chances. I’d park on a side street by his house, facing downhill; then I’d try to do my invisibility thing as I crossed his back yard, hoping not to see a light in the upstairs windows, and not to be reported by some neighbor as a prowler. Dal’s room was like an afterthought to their house—a little room off the kitchen, far away from the rest of the family who were sleeping upstairs. I tapped on his window. No light went on, but he would wave his hand, and in a minute he would raise the window and silently climb out. We didn’t speak until we were across the yard again and inside my car; even then we whispered as if someone might still hear us, and I let the car roll down the hill a block or two, without headlights, making just a faint sound of tires on asphalt, before I started it. Then we would drive all night. We listened to soul music on KATZ, we drove out into the suburbs and kept on until they became country, where the rank plant smell in marshy places reminded me of skunk. We had to be in motion; it was a need like the need to breathe. I felt I was suffocating in the humid wait to get out of St. Louis, out of the whole Midwest—to go East (somehow that was always the direction) and begin what I thought of as another life. Dal seemed to have more patience than I did, but he was ready to leave too. If we didn’t talk about that, then we’d talk about girls, about love. We actually used the word. But then Dal and I had known each other a long time. We drove till we were on the verge of getting lost, and then we turned around and hoped we’d make it back before dawn. On the way back, if there was time and we had any money, we ate hamburgers at some 24-hour diner at five in the morning, and then we sneaked back home into our beds to sleep a couple of hours before we’d meet again at school. Somehow I wasn’t tired the mornings after those nights.

Dal and I didn’t know much about going East, except what we read in books. I’d been to New York just once to visit a cousin, and Dal had never been east of Zanesville, Ohio, but we knew we were going there somehow or other. We knew it was an older part of the world, a place of shrieking subways and even lower, scarier depths. When I thought of New York I thought of a bar over on Delmar Boulevard where there was blue neon over the door and if somebody came out as you were walking by, you’d catch a glimpse of a stairway going down and hear blue music pumping away from below. The opposite of the yellow light in the window at home. I think we wanted to go East to be uncomfortable. At least I did, not for its own sake, but because we believed that a certain kind of discomfort was a sign that you were somewhere near the truth.

Dal and I didn’t know much about love, either, but we knew this much: the authorities were not to be trusted. Whoever said they knew, didn’t; and whoever volunteered to tell us how we should feel, and what we should or shouldn’t do about it, was cordially invited to stick their head in a bucket three times and pull it out twice. Our experience of love was too tentative to bear any impartial scrutiny; I never willingly discussed it with an adult. Anyway, from my point of view it was mostly unrequited, and Claire, my one real girlfriend, had dropped me for someone else. What I dreamed about, it seemed to me Dal could have without even trying; he was surrounded by girls who were waiting for him to notice them. Not that he was aware of it, necessarily. But he could never seem to find what he wanted either. Dal had one thing in mind, true love, which he guarded the same way he guarded his vision of true baseball through an entire game.

Dal pointed out to me more than once that I was always falling in love with unattainable girls, and he, it seemed, was exactly the reverse: he was the unattainable, for various girls who wanted him to ask them out, and even for most of the ones he went out with. I knew. Sometimes more than I wanted to, when Toni or Claire would make it my job to tell Dal about some girl’s crush on him. In the heat of the moment it never seemed to occur to them that the messenger might have feelings about the transaction.

I was pretty much bound to tell him whether they wanted me to or not. Not much could be hidden between me and Dal; it was too late for that. I’d known him since grade school, and we had been inseparable the whole time except for a period when I was his bitter enemy in the fourth grade. I was jealous over something that happened at recess. Dal invented a game called Chaser that he played with a group of kids who were destined to become athletes; they wouldn’t teach it to the rest of us because it was clear we’d never be fast or tricky enough to compete. All we saw was that they darted and bolted from place to place after one another in a bewildering way, their allegiances seeming to shift from second to second, pursuing some strategy I never understood. It was like trying to pick up a tune by watching someone’s fingers play it on the guitar. Dal left me behind, and I hated him. If I could have caught him, I would have jumped up and down on his stomach. But he got bored with Chaser when Little League started up again, and after a while our friendship went back to normal.

When we were in the spring of the sixth grade, Dal and I went to a week-long camp that the school district put on every year for sixth-graders, someplace off in the woods not too far from St. Louis. I suppose they thought of it as a special treat to mark the end of grade school. I don’t know what the girls were up to, but for the boys the real function of this camp, it seemed, was to learn to masturbate and swear. The education took place in the cabins when the organized activities were over. By the time I left I knew every dirty word there was, I’d seen Mark Upton jerk off for a circle of admiring boys who were awed by the size of his penis (and hastily pull up his underpants to hide it when he came, but I didn’t understand that at the time), and a few boys I didn’t know from some other school had even tried to bugger each other, which looked more like a very humiliating form of wrestling than anything else. My own penis was small, like the rest of me, but I found I could do the same thing Mark Upton did, and enjoy it, a discovery that gave a whole new dimension to life.

I wasn’t in a cabin with Dal at camp, so I didn’t get to see how he reacted to all this. I have a feeling he didn’t join in much, but none of it escaped him. He knew what was important to learn.

We had our own private version of that experience, later on; they say all boys do, but no one ever talks about it, that I know of. We must have been in the seventh or eighth grade; at any rate, Dal’s penis was starting to grow and he had sprouted a few pubic hairs, by which I was very impressed. I remember we were at my house alone, looking at an art book full of nudes, and somehow ended up naked ourselves. That’s the part I can’t recall—how we got there, what excuse we made, what game we invented to get our clothes off. But I’m sure that when we were naked, Dal’s erect penis fascinated us both; it was big, and a pearly drop trembled on the tip of it. He lay down on the couch and closed his eyes and said, “Pretend you’re a girl and you’re touching it,” and I did. I still remember the strangeness of the experience and the tentative pleasure it gave me, which, perhaps, was not too different from what I would have felt if I had been an actual girl, and I remember Dal with his eyes closed, absorbed in the power of his sensations, off into a world I couldn’t share yet, only envy and try to imagine.

But we would never have mentioned that even to each other. Having been that innocent, that unselfconscious, was something no one could admit to at seventeen.